Prêt-à-Patria

We know the text, that is to say, the fabric, the cloth from which military uniforms are made. Even as the context changes, still under the camouflage of circumstance, we recognize its weave: the same narrative threads, the same patriotic patterns, the same fascist knots. Here or there, then or now, under one flag or another, we know what it means for someone to be dressed as a soldier, and the body, mine, yours, goes on alert, on guard, as if facing danger, while the soldier's body seems to have disappeared inside the uniform. Because that's what a uniform is for. To erase bodies: theirs, yours, mine; that of the enemy who in the end always turns out to be oneself.

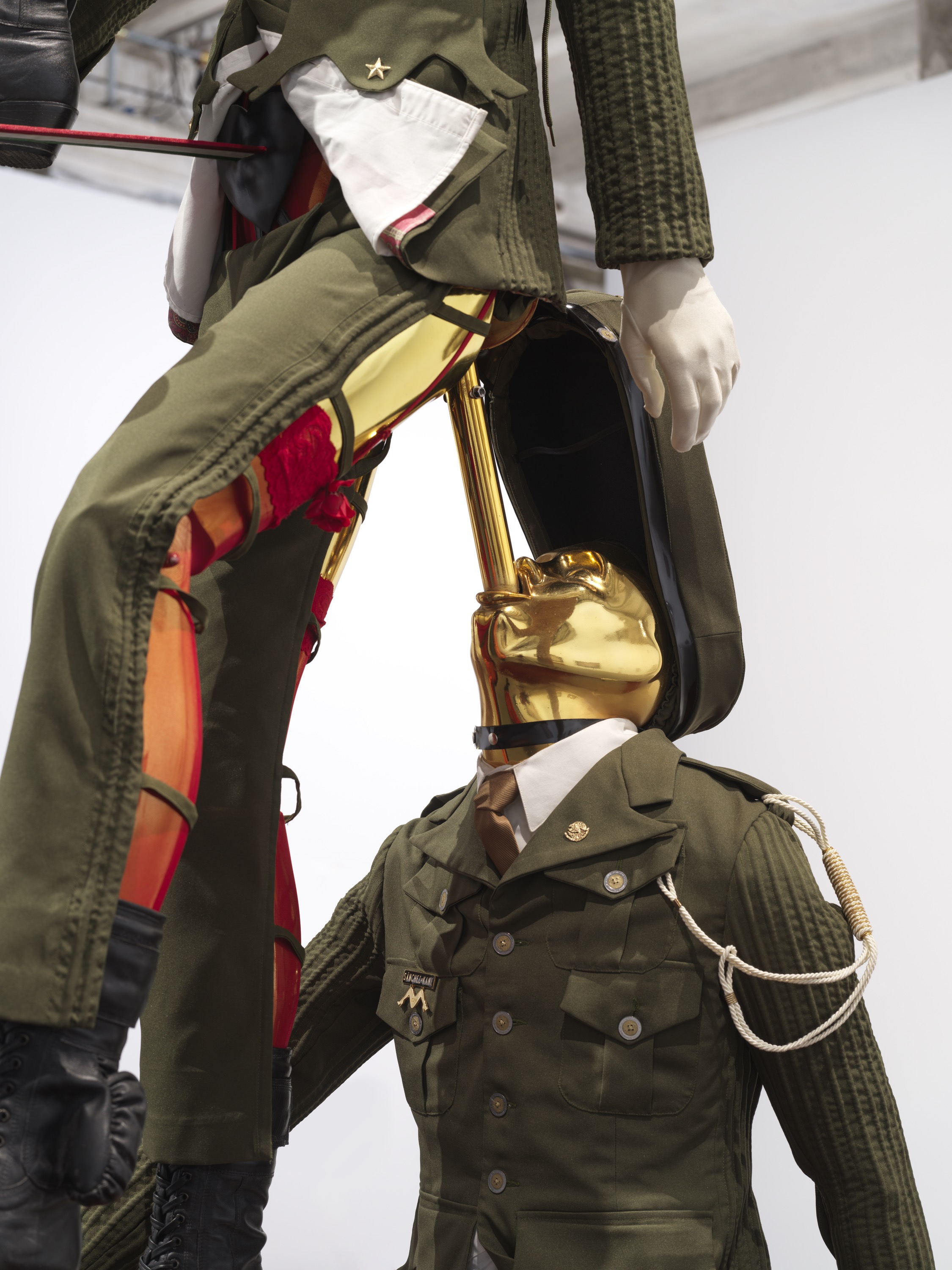

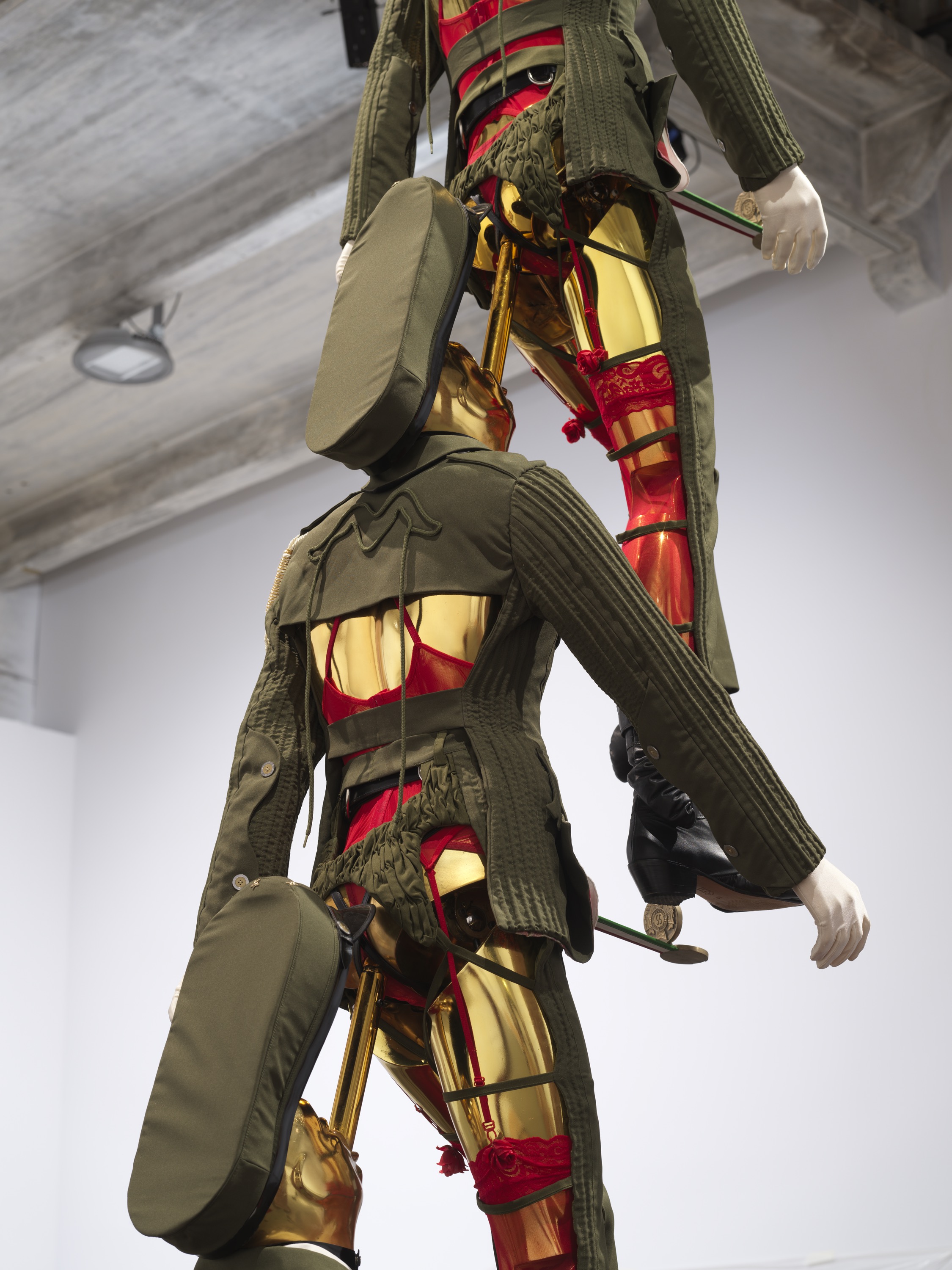

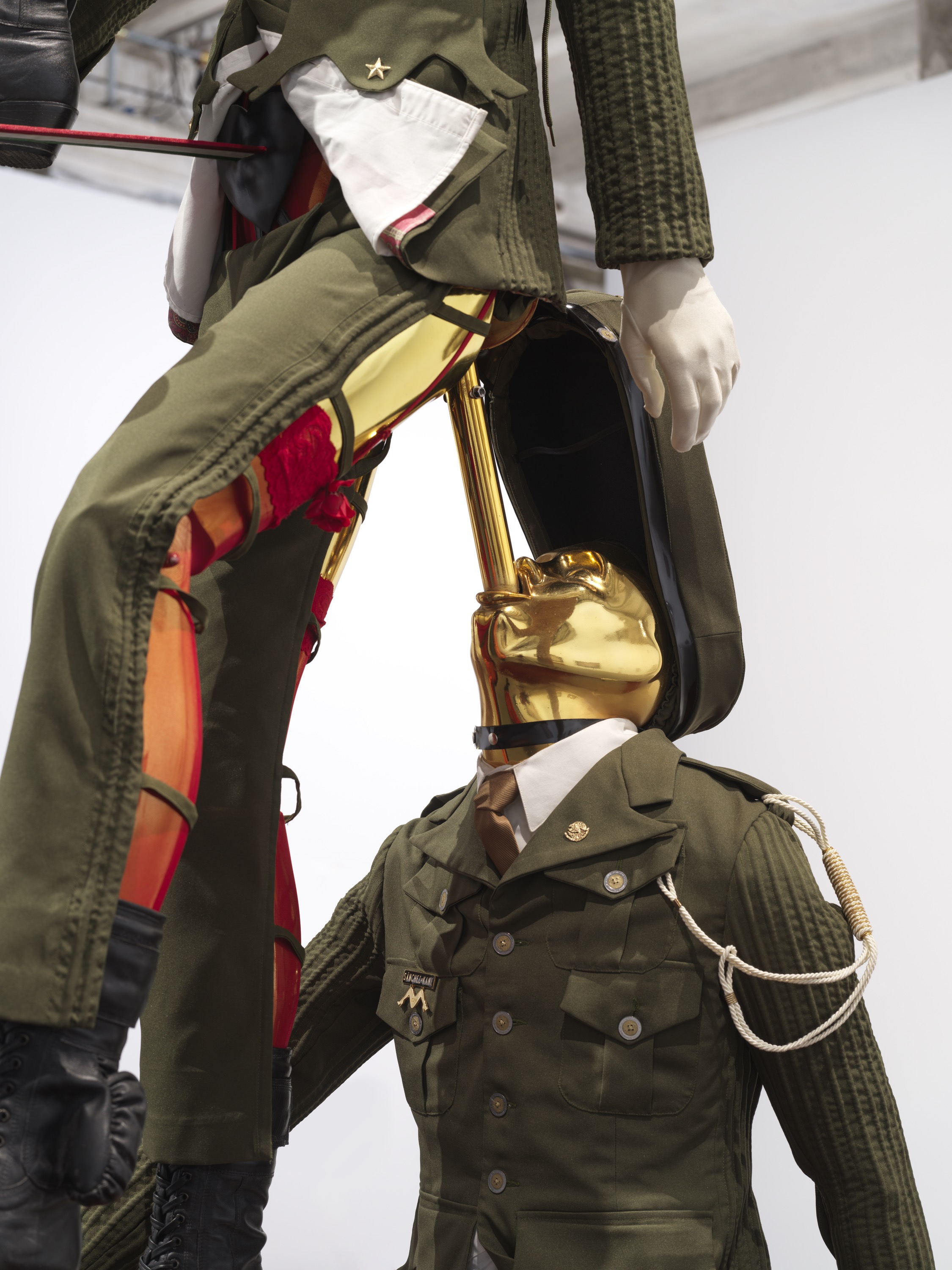

To say, then, that Bárbara Sánchez Kane, in Prêt-à-Patria, makes military uniforms is to say what we already know, that is, nothing. And yes, it's true, Sánchez Kane makes uniforms and she makes them by pushing military paraphernalia to the limit, stretching it to the point of caricature or fetish. The gleaming buttons are coins displaying the Mexican national emblem, but whose exchange value is zero because they have been pierced; the military caps, losing all proportion, have increased in size as if participating in some sort of phallic competition; the boots, with traditional metal tips absent here, have been made with boxing gloves, resembling clown shoes, and their comedic effect is exacerbated by the inefficiency of their impossible padded kicks: violence turned into a clown act. We could say then that the fabric, the text, has folded back onto itself in a self-parodic discourse. But it's not just that. Or not only that.

More than uniforms, what Sánchez Kane creates is a tear. A textual striptease in which military discourse unravels to reveal the truth of a body. The fabric opens like a zipper to the epiphany of flesh in an obscene flash. And so, as, after a wound, when blood spurts forth, the soldier's body reappears, so does the body that the uniform erased from the front. But the one who has been wounded is not the soldier's body but the bodies of those who observe him. Because that other body, in its nakedness emphasized by lingerie, by appealing to us libidinally, includes us. If Eros is depicted armed with bow and arrows, it's because desire is the wound: the horror.

But if the military uniform enables, or at least pretends to, a homogeneity of bodies, neutralizing, by the tailor's art, their differences and peculiarities, making them resemble one model, the mannequin operates in the opposite direction: it's the model of what a body can never become, despite clothing, the gym, diet, purchasing power, military obedience, or aesthetic submission. A piece of clothing will never look as "good" on a body as it does on a mannequin, the mannequin seems to tell us from its indifferent inorganic muteness. We will never resemble the ideal that the mannequin represents. And the body itself, when dressing in the clothing the mannequin exhibited, discovers itself in the fitting room mirror as an aesthetic failure. Unlike the uniform, which is a rule designed for compliance, the mannequin is an impossible standard that can only be aspired to. I don't know which of the two legislations is more atrocious, but Sánchez Kane knows how to disobey and disrupt both. The sculptural mannequins wearing her uniforms exclude us with their ideal proportions and are refractory to our desire, unlike the uniformed bodies of the performative activations and videos of Prêt-à-Patria. And yet, they include us by reflecting us in the round, chromed and polished surfaces of their perfect buttocks peeking through the openings in the clothing. And, as if it were an accidental selfie, they return to us, stripped of certainties, naked of text, our own distorted and grotesque image, if not exact.

Text by Luis Felipe Fabre